Royal Mint (Tower Of London) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Royal Mint is the United Kingdom's oldest company and the official maker of British coins.

Operating under the legal name The Royal Mint Limited, it is a

The history of coins in

The history of coins in

In 1279, the country's numerous mints were unified under a single system whereby control was centralised to the mint within the

In 1279, the country's numerous mints were unified under a single system whereby control was centralised to the mint within the

In 1630, sometime before the outbreak of the

In 1630, sometime before the outbreak of the

Following Charles I's execution in 1649, the newly formed

Following Charles I's execution in 1649, the newly formed

In 1662, after previous attempts to introduce

In 1662, after previous attempts to introduce

Construction started in 1805 on the new purpose-built mint on Tower Hill, opposite the Tower of London, and it was completed by 1809. In 1812, the move became official: the keys of the old mint were ceremoniously delivered to the Constable of the Tower. Facing the front of the site, stood the Johnson Smirke Building, named for its designer James Johnson and builder Robert Smirke. Construction was supervised by the

Construction started in 1805 on the new purpose-built mint on Tower Hill, opposite the Tower of London, and it was completed by 1809. In 1812, the move became official: the keys of the old mint were ceremoniously delivered to the Constable of the Tower. Facing the front of the site, stood the Johnson Smirke Building, named for its designer James Johnson and builder Robert Smirke. Construction was supervised by the

"Ansell, George Frederick (1826–1880)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed 10 February 2017. After the high-level practice as deputy engraver in the Royal Mint, Charles Wiener went then to Lisbon in 1864 as chief engraver to the Mint of Portugal. In 1863 he made a commemorative medal for Prince Albert (1819-1861), consort of Queen Victoria. (Victoria and Albert Museum).

After the high-level practice as deputy engraver in the Royal Mint, Charles Wiener went then to Lisbon in 1864 as chief engraver to the Mint of Portugal. In 1863 he made a commemorative medal for Prince Albert (1819-1861), consort of Queen Victoria. (Victoria and Albert Museum).

As Britain's influence as a

As Britain's influence as a  A fifth branch of the Royal Mint was established in

A fifth branch of the Royal Mint was established in

From 1928, the

From 1928, the

On 1 March 1966, the government announced plans to decimalise the nation's currency, thereby requiring the withdrawal and re-minting of many millions of new coins. At its current site on Tower Hill, the mint had suffered from lack of space for many years, and it would be inadequate to meet the anticipated high demand a recoinage would entail. A possible move to a more suitable site had been discussed as far back as 1870 when Deputy Master of the Mint Charles Fremantle had recommended it in his first annual report. At the time, it had been suggested that the valuable land at Tower Hill could be sold to finance the purchase of land nearby

On 1 March 1966, the government announced plans to decimalise the nation's currency, thereby requiring the withdrawal and re-minting of many millions of new coins. At its current site on Tower Hill, the mint had suffered from lack of space for many years, and it would be inadequate to meet the anticipated high demand a recoinage would entail. A possible move to a more suitable site had been discussed as far back as 1870 when Deputy Master of the Mint Charles Fremantle had recommended it in his first annual report. At the time, it had been suggested that the valuable land at Tower Hill could be sold to finance the purchase of land nearby

Another important operation of the mint, which contributes half the mint's revenue, is the sale of

Another important operation of the mint, which contributes half the mint's revenue, is the sale of

File:The Waterloo Medal MET DP118486.jpg, alt=Waterloo Medal,

limited company

In a limited company, the liability of members or subscribers of the company is limited to what they have invested or guaranteed to the company. Limited companies may be limited by Share (finance), shares or by guarantee. In a company limited by ...

that is wholly owned by His Majesty's Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and e ...

and is under an exclusive contract to supply the nation's coinage. As well as minting circulating coins for the UK and international markets, The Royal Mint is a leading provider of precious metal products.

The Royal Mint was historically part of a series of mints that became centralised to produce coins for the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

, all of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, and nations across the Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

.

The Royal Mint operated within the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

for several hundred years before moving to what is now called Royal Mint Court

Royal Mint Court is a building complex with offices and 100 shared-ownership homes in East Smithfield, in London's East End, close to the City of London financial district.

The site was the home of the Royal Mint from 1809 until 1967 and was ...

, where it remained until the 1960s. As Britain followed the rest of the world in decimalising its currency, the Mint moved from London to a new 38-acre (15 ha) plant in Llantrisant, Glamorgan

, HQ = Cardiff

, Government = Glamorgan County Council (1889–1974)

, Origin=

, Code = GLA

, CodeName = Chapman code

, Replace =

* West Glamorgan

* Mid Glamorgan

* South Glamorgan

, Motto ...

, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

, where it has remained since.

Since 2018 The Royal Mint has been evolving its business to help offset declining cash use. It has expanded into precious metals investment, historic coins, and luxury collectibles, which saw it deliver an operating profit of £12.7 million in 2020–2021.

In 2022 The Royal Mint announced it was building a new plant in South Wales to recover precious metals from electronic waste. The first of this sustainably sourced gold is already being used in a new jewellery division – 886 by The Royal Mint – named in celebration of its symbolic founding date.

History

Origin

The history of coins in

The history of coins in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

can be traced back to the second century BC when they were introduced by Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

tribes from across the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. The first record of coins being minted in Britain is attributed to Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

ish tribes such as the Cantii

The Cantiaci or Cantii were an Iron Age Celtic people living in Britain before the Roman conquest, and gave their name to a '' civitas'' of Roman Britain. They lived in the area now called Kent, in south-eastern England. Their capital was ''Dur ...

who around 80–60 BC imitated those of Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

through casting

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a ''casting'', which is ejected ...

instead of hammering. After the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

began their invasion of Britain

The term Invasion of England may refer to the following planned or actual invasions of what is now modern England, successful or otherwise.

Pre-English Settlement of parts of Britain

* The 55 and 54 BC Caesar's invasions of Britain.

* The 43 AD ...

in AD 43, they set up mints across the land, which produced Roman coins

Roman currency for most of Roman history consisted of gold, silver, bronze, orichalcum and copper coinage. From its introduction to the Republic, during the third century BC, well into Imperial times, Roman currency saw many changes in form, denom ...

for some 40 years before closing. A mint in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

reopened briefly in 383 AD until closing swiftly as Roman rule in Britain came to an end. For the next 200 years, no coins appear to have been minted in Britain until the emergence of English kingdoms in the sixth and seventh centuries. By 650 AD, as many as 30 mints are recorded across Britain.

1279 to 1672

In 1279, the country's numerous mints were unified under a single system whereby control was centralised to the mint within the

In 1279, the country's numerous mints were unified under a single system whereby control was centralised to the mint within the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

. Mints outside London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

were reduced, with only a few local and episcopal mints continuing to operate. Pipe rolls containing the financial records of the London mint show an expenditure of £729 17s 8½d and records of timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

bought for workshops.

Individual roles at the mint were well established by 1464. The master worker was charged with hiring engravers and managing moneyer

A moneyer is a private individual who is officially permitted to mint money. Usually the rights to coin money are bestowed as a concession by a state or government. Moneyers have a long tradition, dating back at least to ancient Greece. They beca ...

s, while the Warden was responsible for witnessing the delivery of dies. A specialist mint board was set up in 1472 to enact a 23 February indenture that vested the mint's responsibilities into three main roles: a warden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically identic ...

, a master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

and comptroller

A comptroller (pronounced either the same as ''controller'' or as ) is a management-level position responsible for supervising the quality of accounting and financial reporting of an organization. A financial comptroller is a senior-level executi ...

.

In the early 16th century, mainland Europe was in the middle of an economic expansion

An economic expansion is an increase in the level of economic activity, and of the goods and services available. It is a period of economic growth as measured by a rise in real GDP. The explanation of fluctuations in aggregate economic activity ...

, but England was suffering from financial difficulties brought on by excessive government spending. By the 1540s, wars with France and Scotland led Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

to enact The Great Debasement, which saw the amount of precious metal in coins significantly reduced. In order to strengthen control of the country's currency, monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

were dissolved, which effectively ended major coin production outside London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

.

In 1603, the Union of Crowns

The Union of the Crowns ( gd, Aonadh nan Crùintean; sco, Union o the Crouns) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas dip ...

of England and Scotland under King James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

led to a partial union of the two kingdoms' currencies, the pound Scots

The pound (Modern and Middle Scots: ''Pund'') was the currency of Scotland prior to the 1707 Treaty of Union between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain. It was introduced by David I, ...

and the pound sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and t ...

. Because Scotland had heavily debased its silver coins, a Scots mark was worth just 13½d while an English mark was worth 6s 8d (80d). To bridge the difference between the values, unofficial supplementary token coin

In numismatics, token coins or trade tokens are coin-like objects used instead of coins. The field of token coins is part of exonumia and token coins are token money. Their denomination is shown or implied by size, color or shape. They are o ...

s, often made from lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, were made by unauthorised minters across the country. By 1612, there were 3,000 such unlicensed mints producing these tokens, none of them paying anything to the government. The Royal Mint, not wanting to divert manpower from minting more profitable gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

and silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

coins, hired outside agent Lord Harington who, under license, started issuing copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

farthings in 1613. Private licenses to mint these coins were revoked in 1644, which led traders to resume minting their own supplementary tokens. In 1672, the Royal Mint finally took over the production of copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

coinage.

Civil War mints

In 1630, sometime before the outbreak of the

In 1630, sometime before the outbreak of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, England signed a treaty with Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

that ensured a steady supply of silver bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from t ...

to the Tower mint. Additional branch mints to aid the one in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

were set up, including one at Aberystwyth Castle

Aberystwyth Castle ( cy, Castell Aberystwyth) is a Grade I listed Edwardian fortress located in Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, Mid Wales. It was built in response to the First Welsh War in the late 13th century, replacing an earlier fortress located ...

in Wales. In 1642, parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

seized control of the Tower mint. After Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

tried to arrest the Five Members

The Five Members were Members of Parliament whom King Charles I attempted to arrest on 4 January 1642. King Charles I entered the English House of Commons, accompanied by armed soldiers, during a sitting of the Long Parliament, although the Fi ...

, he was forced to flee London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

and established at least 16 emergency mints across the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

in Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

, Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

, Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colches ...

, Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

, Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

, Newark

Newark most commonly refers to:

* Newark, New Jersey, city in the United States

* Newark Liberty International Airport, New Jersey; a major air hub in the New York metropolitan area

Newark may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Niagara-on-the ...

, Pontefract

Pontefract is a historic market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wakefield in West Yorkshire, England, east of Wakefield and south of Castleford. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is one of the towns in the City of Wake ...

, Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

, Scarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, su ...

, parts of Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

including Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parishes in England, civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its ...

, Weymouth, Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

, and York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

(see also siege money).

After raising the royal standard in Nottingham

Nottingham ( , East Midlands English, locally ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east ...

, marking the beginning of the civil war, Charles called on loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

mining engineer Thomas Bushell, the owner of a mint and silver mine in Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth () is a university and seaside town as well as a community in Ceredigion, Wales. Located in the historic county of Cardiganshire, means "the mouth of the Ystwyth". Aberystwyth University has been a major educational location in ...

, to move his operations to the royalist-held Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, possibly within in the grounds of Shrewsbury Castle

Shrewsbury Castle is a red sandstone castle in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England. It stands on a hill in the neck of the meander of the River Severn on which the town originally developed. The castle, directly above Shrewsbury railway station, is a ...

. However, this mint was short-lived, operating for no more than three months before Charles ordered Bushell to relocate the mint to his headquarters in the royal capital of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. The new Oxford mint was established on 15 December 1642 in New Inn Hall

New Inn Hall was one of the earliest medieval halls of the University of Oxford. It was located in New Inn Hall Street, Oxford.

History Trilleck's Inn

The original building on the site was Trilleck's Inn, a medieval hall or hostel for stu ...

, the present site of St Peter's College. There, silver plates and foreign coins were melted down and, in some cases, just hammered into shape to produce coins quickly. Bushell was appointed the mint's warden and master-worker, and he laboured alongside notable engravers Nicholas Briot, Thomas Rawlins

Thomas Rawlins (1620?–1670) was an English medallist and playwright.

Life

Born about 1620, Rawlins appears to have received instruction as a goldsmith and gem engraver, and to have worked under Nicholas Briot at the Royal Mint.

Rawlins's fi ...

and Nicholas Burghers, the last of whom was appointed Graver of Seals, Stamps, and Medals in 1643. When Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 (O.S.) / 27 December (N.S.) – 29 November 1682 (O.S.)) was an English army officer, admiral, scientist and colonial governor. He first came to prominence as a Royalist cavalr ...

took control of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

that same year, Bushell was ordered to move to Bristol Castle

Bristol Castle was a Norman castle built for the defence of Bristol. Remains can be seen today in Castle Park near the Broadmead Shopping Centre, including the sally port. Built during the reign of William the Conqueror, and later owned by Rob ...

, where he continued minting coins until it fell to parliamentary control on 11 September 1645, effectively ending Bushell's involvement in the civil war mints.

In November 1642, the king ordered royalist MP Richard Vyvyan to build one or more mints in Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, where he was instructed to mint coins from whatever bullion could be obtained and deliver it to Ralph Hopton

Ralph Hopton, 1st Baron Hopton, (159628 September 1652), was an English politician, soldier and landowner. During the 1642 to 1646 First English Civil War, he served as Royalist commander in the West Country, and was made Baron Hopton of Stra ...

, a commander of royalist troops in the region. Vyvyan built a mint in Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parishes in England, civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its ...

and was its Master until 1646, when it was captured by parliamentarians. In December 1642, the parliamentarians set up a mint in nearby Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

, which had been under parliamentary control since the beginning of the war and was under constant threat of attack by loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

troops. In September 1643, the town was captured by the Cornish Royalist Army

Cornish is the adjective and demonym associated with Cornwall, the most southwesterly part of the United Kingdom. It may refer to:

* Cornish language, a Brittonic Southwestern Celtic language of the Indo-European language family, spoken in Cornwa ...

led by Prince Maurice

Maurice, Prince Palatine of the Rhine KG (16 January 1621, in Küstrin Castle, Brandenburg – September 1652, near the Virgin Islands), was the fourth son of Frederick V, Elector Palatine and Princess Elizabeth, only daughter of King James VI ...

, leading Vyvyan to move his nearby mint in Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parishes in England, civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its ...

to the captured town. The exact location of the mint in Exeter is unknown; however, maps from the time show a street named Old Mint Lane near Friernhay, which was to be the site of a 1696 Recoinage mint. Much less is known about the mint's employees, with only Richard Vyvyan and clerk Thomas Hawkes recorded.

Following Charles I's execution in 1649, the newly formed

Following Charles I's execution in 1649, the newly formed Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

established its own set of coins, which for the first time used English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

rather than Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and were more plainly designed than those issued under the monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

. The government invited French engineer Peter Blondeau Peter Blondeau (french: link=no, Pierre Blondeau; d. 1672) was a French moneyer and engineer who was appointed Engineer to the Royal Mint and was responsible for reintroducing milled coinage to England. He pioneered the process of stamping letterin ...

, who worked at the Paris Mint

The Monnaie de Paris (Paris Mint) is a government-owned institution responsible for producing France's coins. Founded in AD 864 with the Edict of Pistres, it is the world's oldest continuously running minting institution.

In 1973, the mint reloc ...

, to come to London in 1649 in the hope of modernising the country's minting process. In France, hammer-stuck coins had been banned from the Paris Mint since 1639 and replaced with milled coinage

In numismatics, the term milled coinage (also known as machine-struck coinage) is used to describe coins which are produced by some form of machine, rather than by manually hammering coin blanks between two dies (hammered coinage) or casting coi ...

. Blondeau began his testing in May 1651 in Drury House

Drury House was a historic building on Wych Street, London. It was the house of Sir Robert Drury, after whom Drury Lane was named. It was a meeting place for Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex and his accomplices in 1601, when they were plotting ...

. He initially produced milled silver pattern pieces of half-crowns, shillings

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence or ...

and sixpences; however rival moneyers continued using the old hammering method. In 1656, Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

ordered engraver Thomas Simon

Thomas Simon (c. 16231665), English medalist, was born, according to George Vertue, in Yorkshire about 1623.

Simon studied engraving under Nicholas Briot, and about 1635 received a post in connection with the Royal Mint. In 1645 he was appoi ...

to cut a series of dies featuring his bust

Bust commonly refers to:

* A woman's breasts

* Bust (sculpture), of head and shoulders

* An arrest

Bust may also refer to:

Places

* Bust, Bas-Rhin, a city in France

*Lashkargah, Afghanistan, known as Bust historically

Media

* ''Bust'' (magazin ...

and for them to be minted using the new milled method. Few of Cromwell's coins entered circulation; Cromwell died in 1658 and the Commonwealth collapsed two years later. Without Cromwell's backing of milled coinage, Blondeau returned to France, leaving England to continue minting hammer-struck coins.

1660 to 1805

In 1662, after previous attempts to introduce

In 1662, after previous attempts to introduce milled coinage

In numismatics, the term milled coinage (also known as machine-struck coinage) is used to describe coins which are produced by some form of machine, rather than by manually hammering coin blanks between two dies (hammered coinage) or casting coi ...

into Britain had failed, the restored monarch Charles II recalled Peter Blondeau Peter Blondeau (french: link=no, Pierre Blondeau; d. 1672) was a French moneyer and engineer who was appointed Engineer to the Royal Mint and was responsible for reintroducing milled coinage to England. He pioneered the process of stamping letterin ...

to establish a permanent machine-made coinage. Despite the introduction of the newer, milled coins, like the old hammered coins they suffered heavily from counterfeiting and clipping

Clipping may refer to:

Words

* Clipping (morphology), the formation of a new word by shortening it, e.g. "ad" from "advertisement"

* Clipping (phonetics), shortening the articulation of a speech sound, usually a vowel

* Clipping (publications) ...

. To combat this the text ''Decus et tutamen'' ("An ornament and a safeguard") was added to some coin rims.

After the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

of 1688, when James II was ousted from power, parliament took over control of the mint from the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

, which had until then allowed the mint to act as an independent body producing coins on behalf of the government.

Under the patronage of Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax

Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1661 – 19 May 1715), was an English statesman and poet. He was the grandson of the 1st Earl of Manchester and was eventually ennobled himself, first as Baron Halifax in 1700 and later as Earl ...

, Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

became the mint's warden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically identic ...

in 1696. His role, intended to be a sinecure

A sinecure ( or ; from the Latin , 'without', and , 'care') is an office, carrying a salary or otherwise generating income, that requires or involves little or no responsibility, labour, or active service. The term originated in the medieval chu ...

, was taken seriously by Newton, who went about trying to combat the country's growing problems with counterfeiting. By this time, forgeries accounted for 10% of the country's coinage, clipping

Clipping may refer to:

Words

* Clipping (morphology), the formation of a new word by shortening it, e.g. "ad" from "advertisement"

* Clipping (phonetics), shortening the articulation of a speech sound, usually a vowel

* Clipping (publications) ...

was commonplace and the value of the silver in coins had surpassed their face value. King William III

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 16508 March 1702), also widely known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from the ...

initiated the Great Recoinage of 1696

The Great Recoinage of 1696 was an attempt by the English Government under King William III to replace the hammered silver that made up most of the coinage in circulation, much of it being clipped and badly worn.

History

Sterling was in disarr ...

whereby all coins were removed from circulation, and enacted the Coin Act 1696

The Coin Act 1696 (8&9 Will.3 c.26) was an Act of the Parliament of England which made it high treason to make or possess equipment useful for counterfeiting coins. Its title was "An Act for the better preventing the counterfeiting the current Co ...

, making it high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

to own or possess counterfeit

To counterfeit means to imitate something authentic, with the intent to steal, destroy, or replace the original, for use in illegal transactions, or otherwise to deceive individuals into believing that the fake is of equal or greater value tha ...

ing equipment. Satellite mints to aid in the recoinage were established in Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

, Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

, Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

, Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

, and York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, with returned coins being valued by weight, not face value.

The Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union ( gd, Achd an Aonaidh) were two Acts of Parliament: the Union with Scotland Act 1706 passed by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act 1707 passed by the Parliament of Scotland. They put into effect the te ...

united England and Scotland into one country, leading London to take over production of Scotland's currency and thus replacing Scotland's Pound Scots

The pound (Modern and Middle Scots: ''Pund'') was the currency of Scotland prior to the 1707 Treaty of Union between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain. It was introduced by David I, ...

with the English Pound sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and t ...

. As a result, the Edinburgh mint closed on 4 August 1710. As Britain's empire continued to expand, so too did the need to supply its coinage. This, along with the need for new mint machinery and cramped conditions within the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

, led to plans for the mint to move to nearby East Smithfield

East Smithfield is a small locality in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, east London, and also a short street, a part of the A1203 road.

Once broader in scope, the name came to apply to the part of the ancient parish of St Botolph without ...

.

1805 to 1914

Tower Hill

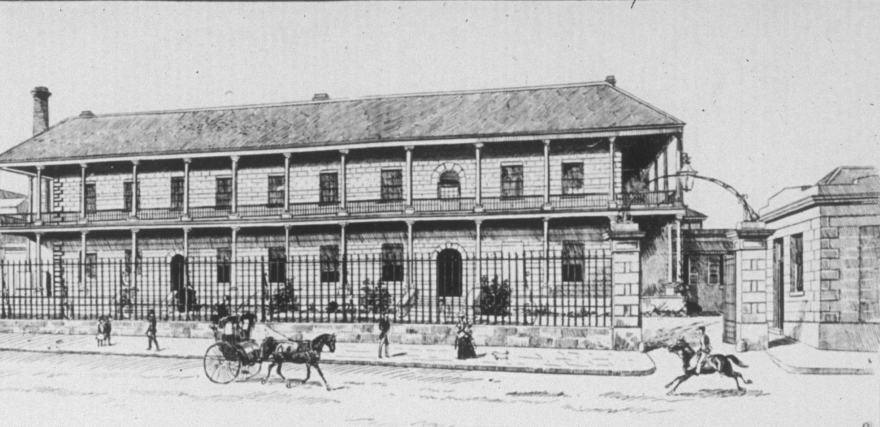

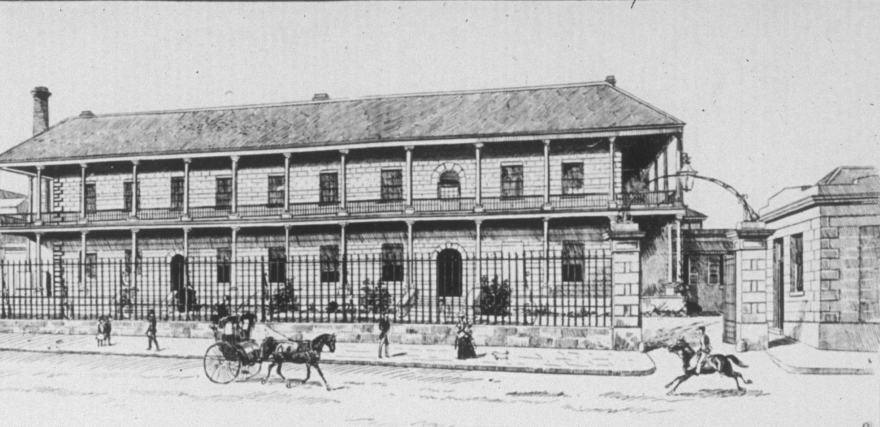

Construction started in 1805 on the new purpose-built mint on Tower Hill, opposite the Tower of London, and it was completed by 1809. In 1812, the move became official: the keys of the old mint were ceremoniously delivered to the Constable of the Tower. Facing the front of the site, stood the Johnson Smirke Building, named for its designer James Johnson and builder Robert Smirke. Construction was supervised by the

Construction started in 1805 on the new purpose-built mint on Tower Hill, opposite the Tower of London, and it was completed by 1809. In 1812, the move became official: the keys of the old mint were ceremoniously delivered to the Constable of the Tower. Facing the front of the site, stood the Johnson Smirke Building, named for its designer James Johnson and builder Robert Smirke. Construction was supervised by the architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

John Lidbury Poole (father of the famous singer, Elizabeth Poole). This building was flanked on both sides by gatehouses behind which another building housed the mint's new machinery. Several other smaller buildings were erected, which housed mint officers and staff members. The entire site was protected by a boundary wall patrolled by the Royal Mint's military guard.

By 1856, the mint was beginning to prove inefficient: there were irregularities in minted coins' fineness and weight. Instructed by Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

, the Master of the Mint Thomas Graham was informed that unless the mint could raise its standards and become more economical, it would be broken up and placed under management by contractors. Graham sought advice from German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann

August Wilhelm von Hofmann (8 April 18185 May 1892) was a German chemist who made considerable contributions to organic chemistry. His research on aniline helped lay the basis of the aniline-dye industry, and his research on coal tar laid the g ...

, who in turn recommended his student George Frederick Ansell to resolve the mint's issues. In a letter to the Treasury dated 29 October 1856, Ansell was put forward as a candidate. He was appointed as a temporary clerk on 12 November 1856, with a £120 a year salary.

Upon taking office, Ansell discovered that the weighing of metals at the mint was extremely loose. At the mint, it had been the custom to weigh silver to within 0.5 troy ounce

Troy weight is a system of units of mass that originated in 15th-century England, and is primarily used in the precious metals industry. The troy weight units are the grain, the pennyweight (24 grains), the troy ounce (20 pennyweights), and the ...

s (oz.) (15.5 g) and gold to a pennyweight

A pennyweight (dwt) is a unit of mass equal to 24 grains, of a troy ounce, of a troy pound, approximately 0.054857 avoirdupois ounce and exactly 1.55517384 grams. It is abbreviated dwt, ''d'' standing for ''denarius'' (an ancien ...

(0.05 oz.); however, these standards meant losses were being made from overvalued metals. In one such case, Ansell delivered 7920.00 oz. of gold to the mint, where it was weighed by an official at 7918.15 oz., a difference of 1.83 oz. Requesting a second weighing on a more accurate scale, the bullion was certified to weigh 7919.98 oz., far closer to the previous measurement, which was off by 960 grains

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit (caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legumes ...

. To increase the accuracy of weights, more precise weighing equipment was ordered, and the tolerance was revised to 0.10 oz. for silver and 0.01 oz. for gold. Between 1856 and 1866, the old scales were gradually removed and replaced with scales made by Messrs. De Grave, Short, and Fanner; winners of an 1862 International Exhibition

The International Exhibition of 1862, or Great London Exposition, was a world's fair. It was held from 1 May to 1 November 1862, beside the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society, South Kensington, London, England, on a site that now houses ...

prize award for work relating to balances.

Ansell also noticed a loss of gold during the manufacturing process. He found that 15 to 20 oz. could be recovered from the sweep, that is, the leftover burnt rubbish from the minting process, which was often left in open boxes for many months before being removed. Wanting to account for every particle and knowing that it was physically impossible for gold just to disappear, he put down the lost weight to a combination of oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

, dust

Dust is made of fine particles of solid matter. On Earth, it generally consists of particles in the atmosphere that come from various sources such as soil lifted by wind (an aeolian process), volcanic eruptions, and pollution. Dust in homes ...

, and different types of foreign matter amongst the gold.

In 1859, the Royal Mint rejected a batch of gold found to be too brittle for the minting of gold sovereigns. Analysis revealed the presence of small amounts of antimony

Antimony is a chemical element with the symbol Sb (from la, stibium) and atomic number 51. A lustrous gray metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (Sb2S3). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient time ...

, arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, but ...

and lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

. With Ansell's background in chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

, he persuaded the Royal Mint to allow him to experiment with the alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductility, ...

, and was ultimately able to produce 167,539 gold sovereigns. On a second occasion in 1868, it was again discovered that gold coins, this time totalling £500,000 worth, were being produced with inferior gold. Although the standard practice at the mint was for rejected coins (known as brockages) to be melted down, many entered general circulation, and the mint was forced to return thousands of ounces of gold to the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

. Although Ansell offered to re-melt the substandard coins, his offer was rejected, causing a row between him and senior mint chiefs, which ultimately led to him being removed from his position at the mint.W. P. Courtney, rev. Robert Brown"Ansell, George Frederick (1826–1880)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed 10 February 2017.

After the high-level practice as deputy engraver in the Royal Mint, Charles Wiener went then to Lisbon in 1864 as chief engraver to the Mint of Portugal. In 1863 he made a commemorative medal for Prince Albert (1819-1861), consort of Queen Victoria. (Victoria and Albert Museum).

After the high-level practice as deputy engraver in the Royal Mint, Charles Wiener went then to Lisbon in 1864 as chief engraver to the Mint of Portugal. In 1863 he made a commemorative medal for Prince Albert (1819-1861), consort of Queen Victoria. (Victoria and Albert Museum).

Royal Mint Refinery

After relocating to its new home on Tower Hill, the Mint came under increased scrutiny of how it dealt with unrefined gold that had entered the country. TheMaster of the Mint

Master of the Mint is a title within the Royal Mint given to the most senior person responsible for its operation. It was an important office in the governments of Scotland and England, and later Great Britain and then the United Kingdom, between ...

had been responsible for overseeing the practice since the position's inception in the 1300s. However, the refinery process proved too costly and suffered from a lack of accountability from the master. A Royal Commission was set up in 1848 to address these issues; it recommended that the refinery process be outsourced to an external agency, thereby removing the refining process from the mint's responsibilities. The opportunity to oversee the Mint's refinery was taken up by Anthony de Rothschild, a descendant of the Rothschild family

The Rothschild family ( , ) is a wealthy Ashkenazi Jewish family originally from Frankfurt that rose to prominence with Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812), a court factor to the German Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel in the Free City of F ...

and heir to the multinational investment banking

Investment banking pertains to certain activities of a financial services company or a corporate division that consist in advisory-based financial transactions on behalf of individuals, corporations, and governments. Traditionally associated wit ...

company N M Rothschild & Sons

Rothschild & Co is a multinational Investment banking, investment bank and financial services company, and the flagship of the Rothschild banking group controlled by the French and British branches of the Rothschild family.

The banking business o ...

. Rothschild secured a lease from the government in January 1852, purchasing equipment and premises adjacent to the Royal Mint on 19 Royal Mint Street under the name of ''Royal Mint Refinery''.

Colonial expansion

As Britain's influence as a

As Britain's influence as a world power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

expanded, with colonies being established abroad, a greater need for currency led to the Royal Mint opening satellite branches overseas. This need first arose in the then-Colony of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, as the black-market trade in gold during and following the 1851 Australian gold rush threatened to undermine the colony's economy. In 1851 the colony's Legislative Council sent Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

a petition seeking a local mint for Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, and in 1853 the Queen issued an Order in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' Ki ...

providing for the establishment of the Sydney Branch of the Royal Mint. The Royal Mint's Superintendent of Coining travelled to Australia to oversee its establishment on Macquarie Street within the southern wing of Sydney Hospital

Sydney Hospital is a major hospital in Australia, located on Macquarie Street in the Sydney central business district. It is the oldest hospital in Australia, dating back to 1788, and has been at its current location since 1811. It first rece ...

, where it opened in 1855. Production increased quickly: assayer's notes from 29 October 1855 indicate that the mint's Bullion Office had purchased of unrefined gold in the preceding week alone, and the mint's overall coin output averaged over £1,000,000 yearly in its first five years of operation. In 1868, gold sovereigns minted in Sydney were made legal tender

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in pa ...

in all British colonies, and in February 1886 they were given equal status in the UK itself.

The success of the Sydney branch led to the opening of similar branches in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

and Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

, on 2 June 1872 and 20 June 1899 respectively. Following the Federation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (which also governed what is now the Northern Territory), and Western A ...

in 1901 and the establishment of a separate Australian pound

The pound ( Sign: £, £A for distinction) was the currency of Australia from 1910 until 14 February 1966, when it was replaced by the Australian dollar. As with other £sd currencies, it was subdivided into 20 shillings (denoted by the symbol ...

in 1910, all three branches were used by the Commonwealth government to mint circulating coins for Australia. The Melbourne and Perth branches had capabilities superior to those in Sydney, and they took over production responsibilities for Australia when the Sydney branch closed after 72 years of operation at the end of 1926. Following the establishment of the Royal Australian Mint

The Royal Australian Mint is the sole producer of all of Australia's circulating coins and is a Commonwealth Government entity operating within the portfolio of the Treasury. The Mint is situated in the Australian federal capital city of Canberr ...

as a central mint for Australian coinage, the Melbourne and Perth mints were divested by the Royal Mint on 1 July 1970.

In Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, which had been under British rule

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was hims ...

since 1763, British coins circulated alongside those of other nations until 1858, when London started producing coins for the newly established Canadian dollar

The Canadian dollar ( symbol: $; code: CAD; french: dollar canadien) is the currency of Canada. It is abbreviated with the dollar sign $, there is no standard disambiguating form, but the abbreviation Can$ is often suggested by notable style ...

. As Canada developed in 1890, calls were made for a mint to be built in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

to facilitate the country's gold mines. The new mint was opened on 2 January 1908 by Lord Grey, producing coins for circulation, including Ottawa Mint sovereign The Ottawa Mint sovereign is a British one pound coin (known as a sovereign) minted between 1908 and 1919 at the Ottawa Mint (known today as the Ottawa branch of the Royal Canadian Mint. This has augmented debate among Canadian numismatists because ...

s. In 1931, under the Statute of Westminster, the mint came under the control of the Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown ...

and was subsequently renamed the Royal Canadian Mint

}) is the mint of Canada and a Crown corporation, operating under the ''Royal Canadian Mint Act''. The shares of the Mint are held in trust for the Crown in right of Canada.

The Mint produces all of Canada's circulation coins, and manufactures ...

. A fifth branch of the Royal Mint was established in

A fifth branch of the Royal Mint was established in Mumbai

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

(Bombay), India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

on 21 December 1917 as part of a wartime effort. It struck sovereigns from 15 August 1918 until 22 April 1919 but closed in May 1919. A sixth and final overseas mint was established in the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

in Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends ...

on 1 January 1923, producing £83,114,575 worth of sovereigns in its lifetime. As South Africa began cutting ties with Britain, the mint closed on 30 June 1941 but was later reopened as the South African Mint

The South African Mint is responsible for minting all coins of the South African rand on behalf of its owner the South African Reserve Bank. Located in Centurion, Gauteng near South Africa's administrative capital Pretoria, the mint manufactures ...

.

Although London's Royal Mint officially controlled just six mints, many more independent mints were set up in parts of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. In New Westminster

New Westminster (colloquially known as New West) is a city in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia, Canada, and a member municipality of the Metro Vancouver Regional District. It was founded by Major-General Richard Moody as the capita ...

, British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

the British Columbia gold rushes British Columbia gold rushes were important episodes in the history and settlement of European, Canadian and Chinese peoples in western Canada.

The presence of gold in what is now British Columbia is spoken of in many old legends that, in part, led ...

led to a mint being established in 1862, by Francis George Claudet

Francis George Claudet (1837-1906) was an assayer for the Royal Mint in British Columbia, Canada, photographer and the youngest son of Antoine François Jean Claudet, the French photographer-inventor who produced daguerreotypes.

Career

Franci ...

, under Governor James Douglas. It produced a few gold and silver coins before being shut down in 1862 to aid the city of Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

in becoming the region's provincial capital

A capital city or capital is the municipality holding primary status in a country, state, province, department, or other subnational entity, usually as its seat of the government. A capital is typically a city that physically encompasses the g ...

. On 26 February 1864, an Order in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' Ki ...

requested the founding of an independent mint (Hong Kong Mint

Hong Kong Mint () was a mint in Hong Kong that existed from 1866 to 1868. Located in Cleveland Street, Causeway Bay, it is the first coin mint of Hong Kong. A Mint Dam, on the slope of Mount Butler, was constructed to supply water to the mint.

I ...

) in British Hong Kong

Hong Kong was a colony and later a dependent territory of the British Empire from 1841 to 1997, apart from a period of occupation under the Japanese Empire from 1941 to 1945 during the Pacific War. The colonial period began with the Briti ...

to issue silver and bronze coins. But this mint was short-lived, due to its coins being heavily debased, causing significant losses. The site was sold to Jardine Matheson

Jardine Matheson Holdings Limited (also known as Jardines) is a Hong Kong-based Bermuda-domiciled British multinational conglomerate. It has a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange and secondary listings on the Singapore Exchange and ...

in 1868, and the mint machinery was sold to the Japanese Mint in Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of 2. ...

.

1914 to 1966

In 1914, as war broke out in Europe,Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

instructed that gold coins be removed from circulation to help pay for the war effort. The government started to issue £1, and 10 shilling Treasury notes as replacements, paving the way for Britain to leave the gold standard in 1931.

From 1928, the

From 1928, the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between th ...

(later the Republic of Ireland) issued its own coins. The Royal Mint produced these until Ireland established its own Currency Centre

The Currency Centre (also known as the Irish Mint) is the mint of coins and printer of banknotes for the Central Bank of Ireland, including the euro currency. The centre is located in Sandyford, Dublin, Ireland. The centre does not print the ...

in Dublin in 1978.

During World War II, the Mint was important in ensuring people were paid for their services with hard currency

In macroeconomics, hard currency, safe-haven currency, or strong currency is any globally traded currency that serves as a reliable and stable store of value. Factors contributing to a currency's ''hard'' status might include the stability and ...

rather than banknotes. Under Operation Bernhard

Operation Bernhard was an exercise by Nazi Germany to forge British bank notes. The initial plan was to drop the notes over Britain to bring about a collapse of the British economy during the Second World War. The first phase was run from early ...

, the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

planned to collapse the British economy

The economy of the United Kingdom is a highly developed social market and market-orientated economy. It is the sixth-largest national economy in the world measured by nominal gross domestic product (GDP), ninth-largest by purchasing power pa ...

by flooding the country with forged notes, leading the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

to stop issuing banknotes of £10 and above. To meet these demands, the Mint doubled its output so that by 1943 it was minting around 700 million coins a year despite the constant threat of being bombed. The Deputy Master of the Mint, John Craig, recognised the dangers to the Mint and introduced several measures to ensure the Mint could continue to operate in the event of a disaster. Craig added emergency water supplies, reinforced the Mint's basement to act as an air-raid shelter

Air raid shelters are structures for the protection of non-combatants as well as combatants against enemy attacks from the air. They are similar to bunkers in many regards, although they are not designed to defend against ground attack (but many ...

and even accepted employment of women for the first time. For most of the war, the mint managed to escape most of the destruction of the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

, but in December 1940 three members of staff were killed in an air raid. Around the same time, an auxiliary mint was set up at Pinewood Studios

Pinewood Studios is a British film and television studio located in the village of Iver Heath, England. It is approximately west of central London.

The studio has been the base for many productions over the years from large-scale films to te ...

, Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

, which had been requisitioned for the war effort. Staff and machinery from Tower Hill were moved to the site, which started production in June 1941 and operated for the duration of the war. Over the course of the war, the Royal Mint was hit on several occasions, and at one point was put out of commission for three weeks. As technology changed with the introduction of electricity and demand continued to grow, the rebuilding process continued so that by the 1960s, little of the original mint remained, apart from Smirke's 1809 building and its gatehouses at the front.

1966 to present

Relocation to Wales

On 1 March 1966, the government announced plans to decimalise the nation's currency, thereby requiring the withdrawal and re-minting of many millions of new coins. At its current site on Tower Hill, the mint had suffered from lack of space for many years, and it would be inadequate to meet the anticipated high demand a recoinage would entail. A possible move to a more suitable site had been discussed as far back as 1870 when Deputy Master of the Mint Charles Fremantle had recommended it in his first annual report. At the time, it had been suggested that the valuable land at Tower Hill could be sold to finance the purchase of land nearby

On 1 March 1966, the government announced plans to decimalise the nation's currency, thereby requiring the withdrawal and re-minting of many millions of new coins. At its current site on Tower Hill, the mint had suffered from lack of space for many years, and it would be inadequate to meet the anticipated high demand a recoinage would entail. A possible move to a more suitable site had been discussed as far back as 1870 when Deputy Master of the Mint Charles Fremantle had recommended it in his first annual report. At the time, it had been suggested that the valuable land at Tower Hill could be sold to finance the purchase of land nearby Whitefriars, London

Whitefriars is an area in the Ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London.

Until 1540, it was the site of a Carmelite monastery, from which it gets its name.

History

The area takes its name from the medieval Carmelite religious house, known ...